(Third in a series. Also: Could I Be Wrong? Social Justice? 11 Strategies for Depolarizing Tomorrow's Citizens.)

During the pandemic, lawn signs appeared on some of my neighbors’ lawns proclaiming what “in this house, we believe.”

The signs were taken by some people to suggest that folks in houses without the signs—and certainly people in houses with Trump signs on the lawn—might think that Black lives don’t matter, that love and science aren’t real, that some humans are illegal, that women aren’t entitled to human rights.

In fact, though, each of what seemed to be incontestable statements of fact—love is love—or unassailable ethical propositions—Black lives matter—were hiding issues over which reasonable, decent people might differ. Wanting more border security doesn’t make you think some humans are illegal. Opposing abortion doesn’t mean you think women don’t deserve human rights.

At the heart of the list is the slogan, expressed elsewhere, “Believe Science,” as if science is a set of uncontested facts that you either believe or don’t.

In fact, the sciences are specialized fields of mostly contested and developing knowledge that are difficult or impossible for most non-specialists to understand, so it’s hard to know which science to believe.

What “believe science” really ends up meaning for most of us is “trust experts” who interpret science for us. Or perhaps more often, “believe journalists” who sift through the various controversies and disagreements among the scientists, and write about it for a general audience in the popular press.

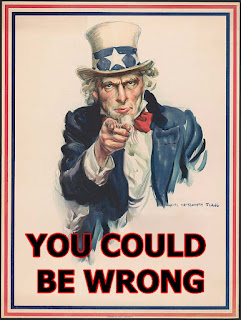

Let’s face it, though, journalists, experts, and even scientists often get things wrong, and so people who don’t share the general liberal inclinations of the vast majority of journalists and credentialed experts and are skeptical of claims to objective neutrality or uncontestable truth, have come up with their own slogan along the lines of “do your own research.”

Even those of us who might be more inclined to rely on experts and journalists surely have to be aware of the many failures of scientific and expert authority.

Not only do scientists disagree with each other on most matters, but even an apparently settled scientific consensus will occasionally get overturned. It seems that every day a new study comes out challenging the existing “science” of human nutrition, for example. Should I avoid fats or not?

When we get away from the hard sciences into social “sciences” like economics, psychology or sociology, the knowledge becomes increasingly shaky, more susceptible to bias, blind spots, social pressure, groupthink, and self-interest.

Perhaps the most consequential recent failure of one of these would-be sciences caused the worst economic disaster since the Great Depression. Some of the most respected economists (think Ivy League) were paid hefty consulting fees to give positive credit ratings to banks that had invested in badly inflated real estate before the melt-down in the market that caused widespread misery during the Great Recession of 2008. In the documentary film, Inside Job, one of the Ivy League professors who took consulting fees to give ill-conceived AAA ratings responds to an interviewer who challenges his integrity by shutting down the interview. He seems offended that anyone would question his righteousness.

Performances like this contribute to a growing disillusionment that leads more and more of us—not to think that science isn’t real—but to question the rule of the educated class of elites who claim exclusive access to scientific understanding. The past 40 years of technocratic rule have led to things like the rust belt, atomization and loneliness, rising homelessness, stagnant wages and a decline in social mobility, deaths of despair, mass incarceration, economic insecurity, declining mortality, obesity, and the collapse of unions. Every institution led by this meritocratic elite has seen a dramatic decline in public confidence.

For the past quarter century, I’ve worked at one of the world’s most prestigious educational institutions, preparing my students to enter the class of the best educated people in the world—our future rulers. One of the most powerful members of the contemporary ruling class, in fact, sat in my classroom for a term.

I’ve had to ask myself if maybe we’ve been doing something wrong in the way we prepare our students to rule. Are we generating hubris in tomorrow’s ruling class? Could it be the inflated grades? The caving in to demanding parents? The constant stream of assembly speakers who call our students the “best and brightest”? Our claim to be teaching “goodness” and “anti-racism” and “social justice” along with knowledge? Or maybe it’s the demanding workload we impose on them. Previous generations of elites didn’t have to work so hard for their diploma and graduated with a better understanding of how their success rested on privilege and class, not just their own merit.

Old alums have told me that they got into Harvard back in the day with C grades at Exeter. Today, only straight-A students get in, but even that’s not enough. They need a long list of extra-curricular achievements, preferably featuring entrepreneurship in the service of a humanitarian cause.

Humility might not come easy to people who have sacrificed their childhoods to a steady stream of achievement and have come out on top in the college admissions Hunger Games (Harvard’s acceptance rate has gone from 30% in 1960 to 3.4% this year). The process makes it “impossible to view success as anything other than the result of individual effort and achievement” and leads inevitably to “meritocratic hubris,” Michael Sandel argues in his book, The Tyranny of Merit.

How did we get to this point? According to Sandel, sometime in the middle of the 20th century, leaders in the field of higher education, led by Harvard president James Conant, campaigned to turn American high schools into “sorting machines” for college admissions’ offices of top universities. Our increasingly complex world was going to need really smart people to run it, he believed, and the most elite colleges and universities would be the place to educate these leaders. High schools should be “reconstructed” for the “specific purpose” of identifying the brainiest students to send to the best colleges. “Abilities must be assessed, talents must be developed, ambitions guided. This is the task for our public schools,” he said (159).

This reconstruction of high school did not achieve Conant’s goal of eliminating class boundaries to the elite. The college admissions system disproportionately rewards children from families that have the resources to pay for enrichment activities that will give their kids an edge, and working class kids are more thoroughly excluded than ever. Notwithstanding all the boasting about diversity, equity and inclusion, a 2017 report by the New York Times showed that 38 of the top colleges in the US had more students from the most affluent 1% of families than from the bottom 60%.

Meanwhile, the elite institutions charged with preparing the meritocracy for leadership “place relatively little curricular emphasis on moral and civic education, or the kind of historical studies that prepare students to exercise informed political judgement about public affairs,” says Sandel, who teaches at Harvard. They rarely ask students to “reflect critically on their moral and political convictions” (192). And yet they also leave those students with a feeling of moral and intellectual superiority to the losers in the competition for credentials—the citizens they will be governing.

Sandel argues for an overhaul of this system. In the meantime, is there something those of us toiling away in its bowels can do to lessen meritocratic hubris?

That’s been the goal of my approach to teaching—especially in my two classes on American government and politics—and of this series of blog posts. Does it have an impact? I’ll surely never know. After reading Sandel’s book, it feels a bit like spitting into the ocean. But it’s worth trying.

The next post in this series will offer a brief outline of the strategies I’ve developed in my puny efforts.

Notes and references on lawn signs, meritocracy, and elite hubris.

The Meritocracy

Michael J. Sandel,

The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good? (2020). A section of the book that particularly resonated with me was “Wounded Winners,” which spoke of the “damaging toll on the winners” in the race for success. He quotes a researcher who says that today, “the most troubled adolescents often come from affluent homes.” Sandel argues that it’s caused by an “unrelenting pressure to perform” (180).

On how the upper middle class has dominated the college admissions game, see Matthew Stewart, “The 9.9 percent is the New American Aristocracy,”

The Atlantic, June 2012.

On income distribution of students at elite schools, see: “The Upshot: Some Colleges Have More Students From the Top 1 Percent Than the Bottom 60,”

New York Times, Jan. 18, 2017.

Lawn signs.

An irony of the lawn signs that promote unquestioning adherence to the dictates of established authority is that they adorn the lawns of people on the left, who in the past were more likely to sport bumper stickers saying: “question authority.” Some more readings on the signs and the sentiments behind them:

Kate Arnoff, in “Believe Science is a Bad Response to Denialism,”

The New Republic, April 27, 2020, wrotes: “Liberals’ glorification of expertise amid the coronavirus and climate crises reveals their own distrust of democracy” and:

Appeals to “capital-s science,” as the theorist Donna Haraway has put it, tap into a basic mistrust of democratic institutions’ ability to navigate uncertain times: trust the experts, and give them whatever they need to get things back to normal. “Both the constructive disagreement intrinsic to science and the adversarial scrutiny necessary to politics disappear in this invocation of science as the ultimate authority—this trick will become familiar in the coming months,” James Butler wrote for the London Review of Books recently. “An extraordinary emergency requires extraordinary powers; no one disagrees with that. But it is politics, not science, which grants these powers legitimacy.”

Hadley Heath Manning, “Your social justice yard sign contributes to division, not discourse,” Denver Post, Sept. 7, 2020: “The signs give cheap cursory treatment to a series of serious issues and imply that only one worldview is acceptable. The signs suggest that, outside of homes displaying them, hatred and bigotry are the norm and only hatred and bigotry can explain any departure from the sign’s political creed.” The signs amount to “collective shaming of those who hold conservative beliefs.”

To understand Manning’s response, it’s helpful to consider Monica Guzman’s discussion of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Human Values. The wording of the lawn signs suggests a one-dimensional moral problem. Either you believe in Justice or equity, or tolerance, or you don’t. In reality, though, each of those issues “puts some fundamentally good values into tension with one another … It’s easy to mistake a different ordering of values for an absence of the ones we care about most—and judge people accordingly.” All policy decisions involve trade-offs between competing goods. See Monica Guzman,

I Never Thought of it That Way: How to Have Fearlessly Curious Conversations in Dangerously Divided Times, 171-172.

Economy experts.

Inside Job, won the Academy Award for best documentary in 2011. It’s hard to watch this film and keep trusting economic experts.

Many academic economists who had advocated for deregulation for decades and helped shape U.S. policy still opposed reform after the 2008 crisis.…. Many of these economists were paid consultants to companies and other groups involved in the financial crisis, conflicts of interest that were often not disclosed in their research papers.

Wikipedia

The essence of the film is captured in this segment about it on the PBS NewsHour.

The clip featuring Glenn Hubbard, Dean of the Columbia business school, gives a flavor of how the film undermines faith in the expertise of academic economists.

Larry Summers is an economic expert—and a former President of Harvard University—who has played an enormous role in shaping policy since the 1990s. In this interview, non-expert John Stewart makes the case that Summers’ policies always squelch inflation in a way that keeps profits flowing to capital at the expense of labor and wages. If you are interested in the relationship between inflation and wages, and an alternative to the policy the FED is following and that Summers favors, see Dean Baker & Jared Bernstein, Getting Back to Full Employment. See also.

We need a revival of the term “political economy,” which acknowledges that there is no one scientific answer to every question about economic policy, but rather that every policy involves trade-offs that help some and hurt others, and so can only be addressed through a political process. When policy makers seek a balance between fighting unemployment and fighting inflation, for example, they will inevitably be making a choice of who benefits from the policy and who has to make a sacrifice (see Danielle Allen’s revealing discussion of sacrifice in the context of unemployment/inflation in Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education, 37-49).

The attempt by the economists to frame their discipline as a hard science revealing laws of nature that must be obeyed, somehow always ends up supporting policies that serve the economic class interests of the economists—or their financial patrons. And it’s not the only field where scientific authority is mobilized in support of a particular group’s economic interests. In the 90s, the FDA’s new Food Pyramid exaggerated the amount of grains you should eat in deference to the interests of agribusiness. See Wikipedia.

The podcast “Pitchfork Economics” seeks to debunk the natural-law conceit of economics.

Health experts

Robert Lustig challenges much of the scientific consensus on human nutrition in Metabolical: The Lure and the Lies of Processed Food, Nutriton, and Modern Medicine, the segment under the heading, “A Fat is Not a Fat,” pp. 187-191, for example, argues that the consensus on saturated fat turns out to be wrong. One of his chapters is entitled “Dietitians Lost Their Mind.” It could be Lustig who turns out to be wrong, of course!

As a close relative of people with chronic disease, I know that the science of medicine is not good at treating it. Often, instead of admitting their lack of understanding, doctors will tell patients who suffer from long-term lingering after-effects of illnesses like Lyme disease or COVID that it is all in their heads. Lisa Miller chronicles this problem in, “The Mystery of Long COVID Is Just the Beginning,” New York Magazine Intelligencer, August 29, 2023. It’s a profile of Lisa Sanders, who was the inspiration for the TV show “House,” and is currently working on diagnosing and treating Long COVID. It’s bad that medical experts don’t understand these sorts of chronic illnesses. It’s worse that doctors dismiss patients’ concerns and tell them it’s psychosomatic. Sanders might consider handing out "I could be wrong" stickers to her fellow doctors. Excerpts:

A tenet of her [Sanders’] value system ... was that doctors should become more comfortable with uncertainty and more willing to cop to what they do not know. “The fact is that, more often than doctors would like to admit, they cannot find a cause for a patient’s symptoms,” she wrote. Unknowing is the first step to solving the puzzle, she believed…

Young doctors, having spent the past three or four years with their heads in their books, can be “ready to feel absolutely certain that they know what to do,” Sanders tells me. …

“Super-success” for Sanders would be to be succeeded in the clinic by a team of young, ambitious doctors who can find the same satisfaction that she does in uncertainty: “At the end of every appointment, every doctor has to ask, What am I going to do for this patient—today—to make it better? It’s a more nuanced question, and the answers come from a not totally absolute sense that you know what to do.”

Some more readings on the misrule of experts

See Ewald Engelen et al., “Misrule of Experts? The Financial Crisis as Elite Debacle,” Center for Research on Socio-Cultural Change, March 2011. The paper questions “the politicized role of technocrats after the 1980s and emphasizes the need to bring private finance and its public regulators under democratic political control whose technical precondition is a dramatic simplification of finance.” The promise of the technocrats is that we can move all kinds of decisions out of the realm of politics into the hands of experts armed with science, creating what James C. Scott calls “antipolitics machines.” See Scott’s, Two Cheers for Anarchism, 111, for a discussion the problem with those machines and a defense of politics.

Christopher Lasch has written extensively about the failure of elites, especially in The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy.

Jesse Singal’s book, The Quick Fix: Why Fad Psychology Can’t Cure Our Social Ills, offers a “powerful indictment of the thought leaders and influencers who cut corners as they sell the public half-baked solutions to problems that deserve more serious treatment” (Amazon blurb). Among other things, Singal argues that a shortage of replication studies is undermining the credibility of social science research.

For a critique of the discipline of sociology that says liberal groupthink—opposing any idea that might be seen as blaming victims—has made the field irrelevant to public policy debates, see Chapter 6 of Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning, The Rise of Victimhood Culture: Microaggressions, Safe Spaces, and the New Culture Wars, "Sociology, Social Justice, and Victimhood."

History is no less subject to these forces, but at least most of us don’t call ourselves scientists. Historians are practicing a humanity. Peter Novick chronicles the misguided and hopefully now abandoned effort to turn history into a science starting in the late 19th century in That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession.

In this 2022 Washington Post op-ed, conservative pundit George F. Will decries the “insufferable and sometimes mistaken certitudes” of the credentialed “mandrins” who set government policy. COVID 19, he writes, “revived, and then weakened, Americans’ reflex of deference” to experts. But then their policies and recommendations “about masks, school closures and economic shutdowns took a toll that is difficult to quantify, but certainly huge, measured in learning loss, blighted lives and the leakage of trust from public life.”

Echoing Sandel, Will argues that the education and career success of these leaders makes them blind to the limits of their own understanding: “in eluding failure they come to ignore their own fallibility.”

In a recent piece in the Times, Sam Adler-Bell, the liberal historian of conservatism and co-host of the excellent podcast on conservative thinkers, “Know Your Enemy,” discusses the political power of anti-elitism in the Republican Party, and how it favors Trump at the expense of DeSantis in the upcoming presidential primary, revealing a schism between party leaders and most of their voters.

Mr. DeSantis has managed to corral key Republican megadonors, Murdoch media empire executives and conservative thought leaders from National Review to the Claremont Institute. He polls considerably higher than Mr. Trump with wealthy, college-educated, city- and suburb-dwelling Republicans. Mr. Trump, meanwhile, retains his grip on blue-collar, less educated and rural conservatives. For the G.O.P., the primary fight has begun to tell an all-too-familiar story: It’s the elites vs. the rabble.

Mr. Trump, for his part, appears to have taken notice of this incipient class divide (and perhaps of the dearth of billionaires rushing to his aid). In the past few weeks, he has skewered Mr. DeSantis as a tool for “globalist” plutocrats and the Republican old guard. Since his indictment by a Manhattan grand jury, Mr. Trump has sought to further solidify his status as the indispensable people’s champion, attacked on all sides by a conspiracy of liberal elites. While donors and operatives may prefer a more housebroken populism, it is Mr. Trump’s surmise that large parts of the base still want the real thing, warts and all.

If his wager pays off, it will be a sign not just of his continued dominance over the Republican Party but also of something deeper: an ongoing revolt against “the best and brightest.”

Meanwhile, DeSantis seems to share the elite snobbery toward the “rabble” that Trump has mobilized against:

In his 2011 book, Mr. DeSantis railed against the “‘leveling’ spirit” that threatens to take hold in a republic, especially among the lower orders. His principal target in the book is “redistributive justice,” by which he apparently means any effort at all to share the benefits of economic growth more equitably—whether using government power to provide for the poor or to guarantee health care, higher wages or jobs.

This profile of Naomi Klein in the Times illustrates how the left wing “question authority” mistrust of elite rule has been adopted and transformed by conspiratorially minded thinkers on the right: Grant Harder, “When Your ‘Doppelganger’ Becomes a Conspiracy Theorist,” New York Times Magazine, Aug. 30, 2023. The essay tells the story of how radical left-wing author and activist Naomi Klein’s “doppelganger,” Naomi Wolf, has taken some of her ideas and turned them into conspiracy theories appealing to the right.

As much as Klein recoiled at what Wolf was saying, she also felt the sting of recognition. Klein recalls the uncanny spectacle of seeing a version of her systems-level thesis in “The Shock Doctrine—that elites will take advantage of a crisis to impose their will—twisted by the likes of Wolf, who has described COVID as “a much-hyped medical crisis” that “has taken on the role of being used as a pretext to strip us all of core freedoms.” Klein became both obsessed and repulsed, fascinated and appalled: “I felt like she had taken my ideas, fed them into a bonkers blender and then shared the thought-purée with Tucker Carlson, who nodded vehemently.”

The widespread erosion of faith in any kind of reliable version of reality is a big problem. This piece in the Times shows just how far such skepticism can be taken. Tiffany Hsu, “Falsehoods Follow Close Behind This Summer’s Natural Disasters,” Aug. 30, 2023.

This series: Part 1: Could I Be Wrong? (civics education and epistemic humility); Part 2: Social Justice? (Teaching citizenship to students with different values) and Part 3: Believe Science? (curbing meritocratic hubris in tomorrow's leaders); Part 4: 11 Strategies for Depolarizing Tomorrow's Citizens.