Rarely has there been a national emergency with the potential to unite the country in universal sacrifice like this one. In my sixtieth year, this is the first time I’ve been required to make any significant personal sacrifice as a citizen. I was too young for the Vietnam draft and our many wars since then have been fought by volunteers. We were told that our only patriotic duty after 911 was to keep shopping. Now we are all being asked to stay at home and sacrifice our plans, our normal routines, social gatherings, and even to drastically curtail shopping. And if we fail at it, if we can’t get ourselves to keep a six-foot social distance—the hospitals will be overwhelmed and hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens will die.

Not all of us are being asked to sacrifice equally. Some are managing to keep our jobs and won’t have to worry about paying the monthly rent. Others are losing their livelihoods. Health care workers risk being infected every day at work.

And not everyone is going along with the plan—those spring break revelers, for example, or the toilet paper hoarders. In a past war, they might have been called “slackers.”

There were quite a few slackers in the First World War, which happened to coincide with the last major flu pandemic, when the accompanying photograph was taken. That’s why the federal government felt the need to run a major propaganda campaign with posters like the one in the background of the photograph. Some outspoken opponents of the war, like Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs, were thrown in jail; “slackers” faced community censure, and in at least one extreme case, death by mob violence for failing to purchase a “liberty bond.”

In World War II the American people got closer to unanimously embracing sacrifice in the national interest than they ever have, before or since. Beating Nazis was something we could pretty much all get behind.

You might think that beating the deadly coronavirus could inspire a similar degree of national unity and willing sacrifice. But instead the nation is divided and ambivalent about what should be done and who should sacrifice what. Only recently has the President himself gotten fully behind the drastic social distancing measures that professional health experts are calling for, but he could do more to define it as a patriotic duty and call out those who don’t do their part as something like slackers. It’s Trump’s most enthusiastic supporters, after all, who are putting up the most resistance to social distancing, egged on by the pro-Trump media.

Part of the problem is uncertainty. Instead of an enemy shooting at us with bullets and bombs, we are fighting invisible germs, and our response is based on statistical modeling by health experts, which most of us can only take on faith—at a time when many of us have lost faith in expertise.

And that uncertainty leads to questions about the validity of the sacrifices we are making. The president himself can’t seem to decide whether it’s all really worth it. He said just a short while ago, “we cannot let the cure be worse than the problem itself.” Or as Glen Beck put it, “I would rather die than kill the country.”

And I confess to having had my own doubts. How do we weigh the suffering caused by over-burdened health care workers and a perhaps massive rise in virus deaths against the cost of shutting down the economy? The latter leads to real suffering too, and it has already begun, with 10 million losing their jobs (and health care coverage?) in the past two weeks, students struggling to adjust to online learning (a struggle I’ve witnessed; it’s not pretty), rents and mortgage payments coming due, small businesses ordered to close, victims of mental illness cut off from needed therapy.

This suffering is reflected in the headlines: “Some cities see jumps in domestic violence during the pandemic,” one CNN headline proclaims. And I have seen it in person: the store clerk who said his cancer treatment has been postponed, the 20-somethings in my orbit whose launch has been interrupted, the small businesses in my neighborhood that have had to shut down. Meanwhile people I know personally who have the virus have so far had only mild cases and been told by doctors not to come in for treatment or even testing.* Are such cases being factored into the experts’ models, I wonder?

But then the other day I listened to a

Throughline podcast about the 1918 pandemic, which mentioned the photograph of the nurses making masks. The Red Cross poster on the wall behind them defines virus transmission-mitigation measures—like making masks—as a patriotic duty. More Americans died in that pandemic than in either of the World Wars. I got to thinking that instead of feeling put upon about the sacrifices we are enduring now, what if we could manage to feel patriotic and ever so slightly heroic about doing our part in preventing that from happening again?

That sense of shared sacrifice for a worthy goal is something we have not experienced as a nation in a long time. Since Vietnam, the burdens of war have fallen on an ever shrinking number of citizens. And there have been very good reasons to oppose wars like the one in Vietnam. For once, defeat of the enemy we face today—certainly a just cause—requires something of all of us. We may not be suffering equally, but we are pretty much all suffering to some extent.

In her great meditation on democracy,

Talking to Strangers, Danielle Allen shows how sacrifice is key to the survival of a system where the people vote. It is the willingness of the losers to abide by the results of elections that allows the system to survive. Allen writes:

An honest account of collective democratic action must begin by acknowledging that communal decisions inevitably benefit some citizens at the expense of others, even when the whole community generally benefits. Since democracy claims to secure the good of all citizens, those people who benefit less than others from particular political decisions, but nonetheless accede to those decisions, preserve the stability of political institutions. Their sacrifice makes collective democratic action possible…. The hard truth of democracy is that some citizens are always giving things up for others. (28-29)

Allen shows how some Americans have been asked to sacrifice more than others. Since the 1970s, for example, rust belt workers lost livelihoods in manufacturing jobs when the majority embraced free trade and globalization. When such unequal sacrifice is not acknowledged by those who benefit from it, she argues, trust among citizens is eroded and the survival of democracy is at risk.

I would imagine she might see moments in our national life when we all have to sacrifice something for the greater good as an opportunity to build trust and solidarity and strengthen democracy.

It is unfortunate that we are all still so far from unanimously embracing as patriotic the sacrifices currently being asked of us. But a corner may have been turned on the last day of March, when the president seemed to abandon his ambivalence about what needs to be done and to ask us all to make sacrifices for the greater good. Here are his opening remarks in that day’s Coronavirus Task Force Press Briefing:

Our country is in the midst of a great national trial, unlike any we have ever faced before. You all see it… We’re at war with a deadly virus. Success in this fight will require the full, absolute measure of our collective strength, love, and devotion. Very important. Each of us has the power, through our own choices and actions, to save American lives and rescue the most vulnerable among us. That’s why we really have to do what we all know is right. Every citizen is being called upon to make sacrifices. Every business is being asked to fulfill its patriotic duty. Every community is making fundamental changes to how we live, work, and interact each and every day.

Those good words—including “sacrifice”—are a start, but need to be followed up with many more words and actions—and really a wholly different approach to presidential leadership. Since Trump has shared their skepticism about drastic measures to slow the spread of coronavirus he may be the only person who could get the opponents of those measures on board with the program. And then maybe the collective experience of sheltering in place will help us see the way that sacrifices are not equally borne by all, and that could do something to restore trust among citizens, in their government, and in democracy. Hope springs eternal!

More food for thought:

Danielle Allen has a column in the

Washington Post. She has written four

essays on the pandemic starting on March 13. And her book is worth reading. I haven't done it justice here at all. In fact I think I need to read it again:

Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education (2006)

This

Atlantic essay by McCay Coppins offers a sobering look at how our pre-existing political divisions are reflected in our reactions to the pandemic.

"The Daily," (podcast of the NY Times) ran a

segment on the leadership of governors, many of whom spoke about the role of sacrifice in managing the pandemic.

On the point that the sacrifices are not equally shared, listen to

Bob Garfield’s hilarious send-up of celebrities and how they are coping with social distancing.

This recent

Ezra Klein podcast featured sociologist Eric Klinenberg discussing the real suffering and sacrifice involved in social isolation. They also discuss the ways that some of those who are being asked to make the most sacrifices for others happen also to be people that society was treating pretty shabbily up to now.

Someone asked if by saying "some of us" when referring to rising mistrust of experts meant that I shared that mistrust. The answer is yes, to a point, though, as in the present crisis, we nonetheless often have no choice but to rely heavily on expert advice. Just one example of the problem with expertise—the financial experts who were largely to blame for the last great recession. See, for example,

this PBS Newshour segment.

*Postscript: On April 11 (last night), I learned of the first death of a person close

to me. Since I wrote the blog post, above, the predicted acceleration

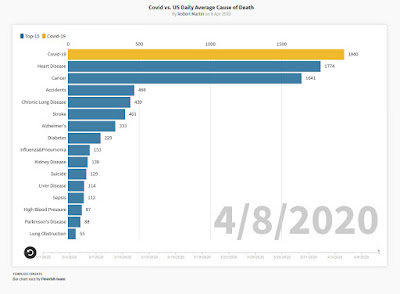

of coronavirus has arrived. A friend, also yesterday, posted this

graphic representation that drives the point home. Click on the image

and watch the daily death toll rise over time.

Update. On his release from the hospital after surviving the coronavirus, Boris Johnson delivered

this video address to the nation on April 12. I think it is a model of democratic leadership in the way that it acknowledges sacrifice. It's hard for me to to imagine citizens listening to this and then refusing to cooperate with social distancing measures being asked of them.